The Bauhaus school

- The art school was founded in 1919 in Weimar. It moved to Dessau in 1926 and then to Berlin in 1932, before the Nazis closed it down in 1933.

- Exerted tremendous influence on modern architecture, design and art in its time and up to the present.

- Also heavily influenced graphic design and typography.

- Based on the idea of creating "Gesamtkunstwerk", or "total work of art”, which aimed to combine all art forms, including architecture.

- Was concerned with the principle of "art for everyone" and "Neue Sachlichkeit" (new objectivity), rationality, simplicity and functionalism.

- Well-known teachers at the school included Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy and Hannes Meyer.

- The word Bauhaus comes from the German word Hausbau, which means "house building".

- Celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2019 with several major exhibitions internationally and at the National Museum – Architecture with an exhibition and a lecture by Widar Halén.

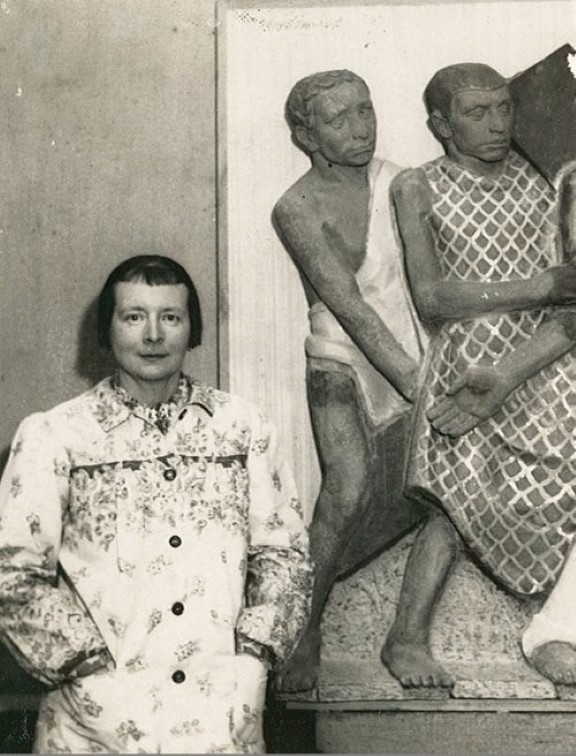

Maja Refsum with relief for Oslofjord, 1930's. © Oslo Museum

Photo: Ukjent / Unknown

Iconic tea services

Marianne and Erik Brandt in the Blomqvist’s Galleri, Oslo, 25.4.1930. © Bauhaus Archiv, Berlin.

Photo: Ukjent / Unknown

Thorbjørn Lie-Jørgensen, pitcher for hot chocolate, silver and ebony, David-Andersen (manufacturer), 1934.

Photo: Nasjonalmuseet

Otti Berger and a friend on a Bauhaus Dessau balcony, 1931-32.

Photo: Ola Mørk Sandvik

A Norwegian on a motorcycle

Ola Mørk Sandvik, from private photo album.

Photo: Ola Mørk Sandvik

Today Sandvik is perhaps best known for Slemdal school, built in 1939. He was also an assistant on Finn Bryn and Johan Ellefsen's project for a new vestibule in the Physics building at Blindern and worked especially with the interiors. This is a building that is clearly inspired by Bauhaus.

– Widar Halén

Arne Korsmo, «Villa Benjamin», 1935. Unknown year for photo. © Teigen, Karl/DEXTRA Photo

Photo: Teigen Fotoatelier

"Flat roofs are unGerman"

When did they live?

Bauhaus professors and directors:

- Walter Gropius (1883–1969)

- Oscar Schlemmer (1888–1943)

- Leyonel Feininger (1871–1956)

- Paul Klee (1879–1940)

- Georg Marcks (1889–1981)

- Ludwig Hilberseimer (1885–1967)

- Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944)

- Gunta Stölzl (1897–1983)

- Georg Muche (1895–1987)

- László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946)

Bauhaus students referred to above:

- Otti Berger (1898–1944/45)

- Ola Mørk Sandvik (1911–1993)

- Hans Mollø-Christensen (1912–1971)

- Maja Refsum (1897–1986)

- Marianne Brandt (1893–1983)

- Erik Brandt (1897–1947)

- Arne Korsmo (1900–1968)

- Grete Prytz (1917–2010)

Other Norwegians who were influenced by Bauhaus:

- Hanna Visund (1881–1974)

- Finn Bryn (1890–1975)

- Herman Munthe-Kaas (1890–1977)

- Sigurd Alf Eriksen (1899–1991)

- Finn Nielssen (1908–1962)

- Carl Nesjar (1920–2015)

- Thorbjørn Lie-Jørgensen (1900–1961)