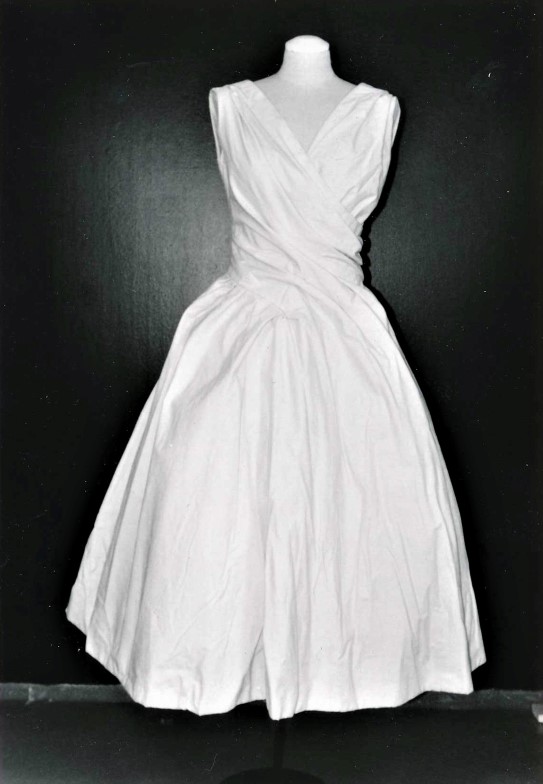

This was not a total waste of money for the Norwegian fashion houses. The payment served as a kind of deposit, guaranteeing that the companies would purchase products equivalent to the amount of the admission fee. This amount did not buy them a complete collection, however. The sum included one original Dior creation, two samples in cotton – so-called toiles – or three paper patterns. The test samples and patterns allowed buyers to produce their own copies, so-called licenced versions, also referred to as bonded couture models. Since the original outfits were often too small for Norwegian customers, the Norwegian buyers preferred toiles and paper patterns. Toiles also had the advantage of demonstrating both construction and seams, as well as the various fabric layers.

This form of licencing was an attempt by Dior to prevent piracy by offering original designs to European and American fashion houses. Having the rights to the licenced copies also conferred great prestige on the buyers.

Licenced production of Parisian fashion was common in Norway between 1950 and 1970. Later, the fashion industry faced fiercer competition from manufacturers of mass-produced garments, and the Norwegian companies closed down what were referred to as their model salons. This is where they had produced tailor-made clothing according to French and in-house designs. Over time, this chapter in Norwegian fashion history ended up in the museum.

Piracy

- Fashion design piracy is a phenomenon as old as the fashion industry itself.

- Pirate copying of dresses from the major fashion houses was also a big problem even before WWII.

- Madeleine Vionnet and Coco Chanel were among those who spearheaded moves to stop design piracy. They fought for stricter legislation and tried out different licencing schemes.

- In the period before and after WWII, the fashion industry was one of France's most important sources of income. This has meant that the country today has some of the world's most stringent laws for protecting fashion designs.

Dior in the National Museum's collection

- The National Museum has a total of 25 Dior objects in its collection.

- Nine of these are toiles.

- Eight are actual garments.

- Seven are pairs of shoes and accessories.

- There is also one paper pattern.

- Most of the museum's garments were made in Norway, often by Molstad, but also at Silkehuset and Steen & Strøm.