Childhood dream

She started an embroidery business to earn a living. She soon came across some old Telemark coverlets that required repair.

She became fascinated by traditional woven textiles with local patterns. She quickly learned to weave, and in the years that followed she established a new foundation for the future of Norwegian textile art.

Frida Hansen

- Frederikke Bolette (called Frida) Hansen, born Petersen

- Born: 8 March 1855 in Hillevåg in Stavanger

- Learned weaving from Kjerstina Hauglum in Sogn

- Established Norway's first natural dye works in Stavanger in 1889

- Founded Atelier for haandvævede norske Tæpper (Studio for Handwoven Norwegian Tapestries) in 1890

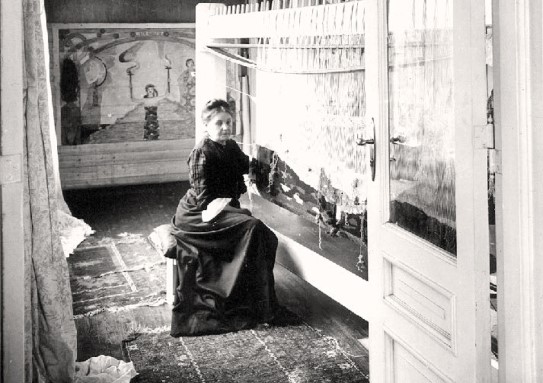

- Established a weaving studio at Tullinløkka in Oslo in 1892

- Established the limited company Norsk Aaklæde – og Billedtæppe-Væveri (Norwegian Coverlet and Tapestry Weaving Mill) together with Randi Blehr in 1897

- Patented the weaving technique Transparents (Transparence) in 1897

- Awarded the King's Medal of Merit in gold in 1915

- Died 12 March 1931 in Oslo

Her very own colour palette

An independent artistic expression

The Studio

The magazine The Studio: An illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art was first published in England in 1893. It showcased the most prominent artists, architects and designers of the time. Frida Hansen subscribed to The Studio, which was an important source of inspiration.

A transparent technique

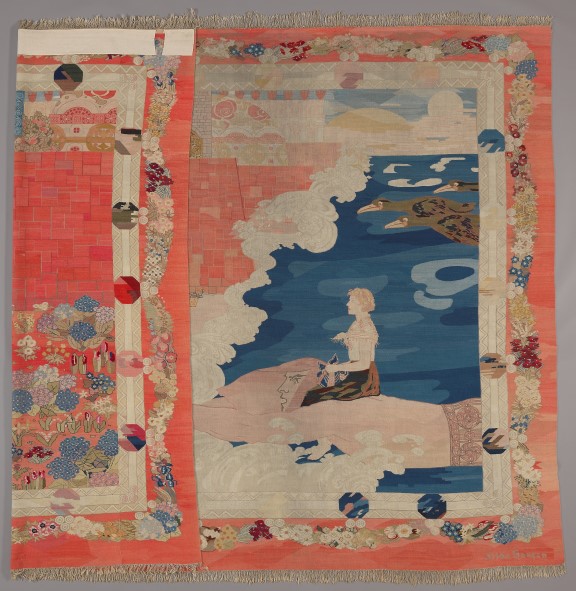

In 1897, Frida Hansen patented her transparent technique where she alternated between dense and translucent parts in the weave. This decorative technique allowed her love for flowers and organic plants to fully blossom. The airy and elegant textiles became very popular and could be used as room dividers and curtains.

Un-Norwegian?

Hansen's tapestries were enthusiastically embraced abroad, but at home her work was often criticised for being "un-Norwegian". In the time around the dissolution of the union with Sweden, decorative artists were expected to reflect Norwegian national identity. Gerhard Munthe's textile patterns were popular, taking their inspiration from Norwegian folk tales, legends and stories from Viking times and the Middle Ages.

Frida Hansen was also influenced by national themes, but was particularly associated with international impulses that were opposed to creating a national identity. This was the reason why her works were purchased by most of the major museums in Europe but were not recognised by Norwegian museums until much later.