Be social

From the beginning of the 1990s, Bourgeois held salon conversations at her own home. She invited young artists and offered them the possibility to give each other feedback on their artworks in production. For the artists, it was a major honour to be invited to the legendary Sunday salons.

"She was keen to get to know other artists and surrounded herself with younger artists throughout her life", says Senior Curator Andrea Kroksnes, one of the curators of the exhibition "Louise Bourgeois. Imaginary conversations" at the National Museum.

Kroksnes also refers to how Bourgeois was an outspoken feminist in the 1970s and was praised by other feminist artists for her fight for their rights and the right to use explicitly sexual motifs.

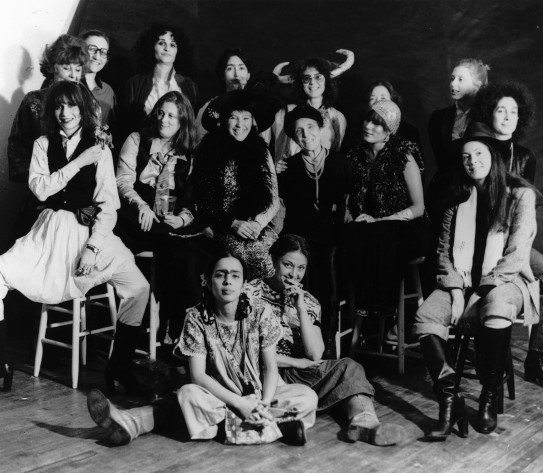

In 1979, artists Ana Mendieta and Mary Beth Edelson organised a feminist party in honour of Bourgeois. The invited women were asked to come dressed "as their favourite artist", and several of them chose – with a twinkle in their eye – to come as themselves.

"Louise never hung out with older people. She only hung out with younger people", says Jerry Gorovoy.

Perhaps the continuous stimulation from younger artists helped Bourgeois retain her playful spirit?

Curator Learning for the Bourgeois exhibition at the National Museum, Elin Therese Aarseth, likes a piece of advice Bourgeois gave when she was asked what advice she would give younger artists, as quoted by The Associated Press in 2008:

"Tell your own story, and you will be interesting, Don't get the green disease of envy. Don't be fooled by success and money. Don't let anything come between you and your work".

"I was sort of hooked by Louise when I met her. She was 69–70, but she had the energy, a spark in the eye, of someone much younger. I never felt her as an older person", says Gorovoy.

Let your feelings out