Otti Berger in the Weaving Workshop at Bauhaus Dessau, 1930-32. © Gertrud Arndt: VG Bild- Kunst Bonn

Photo: Gertrud Arendt

Otti Berger, student work Tasttaffel, composed of different types of yarn with pieces of paper on a metal mesh background, 1928.

Photo: Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin / Atelier Schneider

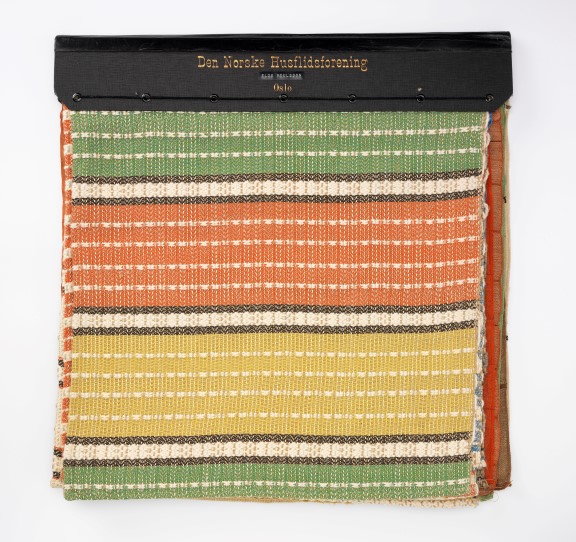

Else Poulsson, interior textiles, cotton and artificial silk, Den Norske Husflidsforening, ca. 1937.

Photo: Nasjonalmuseet / Frode Larsen

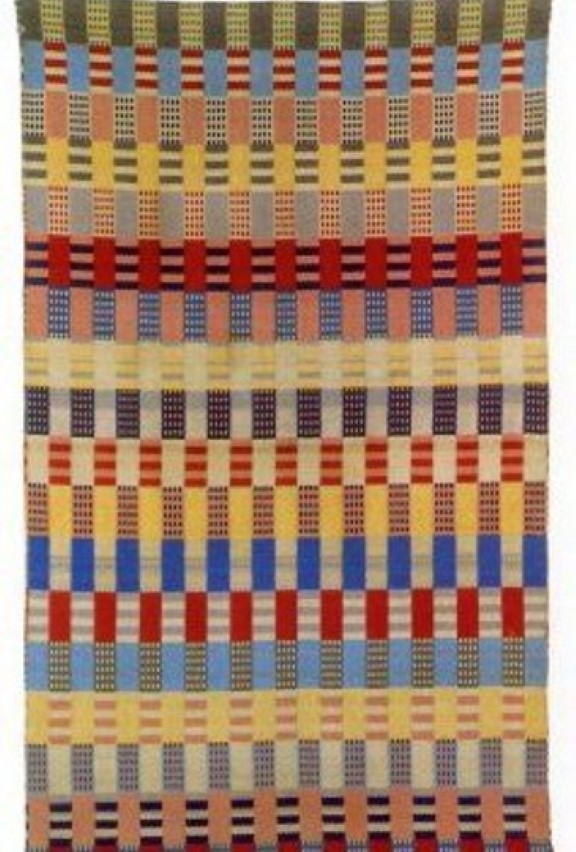

Otti Berger, children's blanket, cotton, Bauhaus Dessau, 1929.

Photo: May Vogt / Bpk/Kunst-sammlung Chemnitz.

Otti Berger, Diagonalstoffe, Bauhaus nr. 209/1, cotton and artificial silk, ca. 1930.

Photo: Atelier Schneider / Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin

Otti Berger, (attributed), curtain, cotton, produced by De Ploeg, Bergeijk, The Netherlands, 1933–1937. Siljustøl.

Photo: Dag Fosse / KODE

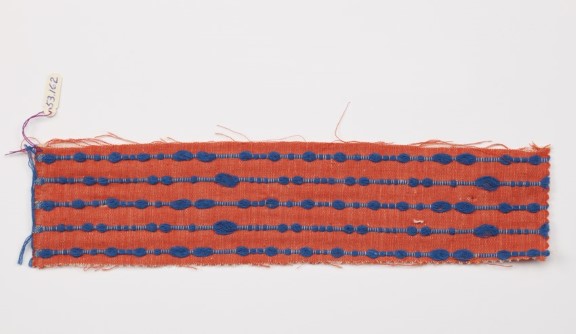

Otti Berger, textile, cotton, produced by De Ploeg, Bergeijk, the Netherlands, 1933–1937.

Photo: RIDS Museum, Rhode Island, USA

Åse Eriksen, duplicate weaving of curtain, 2004, Siljøstøl, KODE.

Photo: Dag Fosse / KODE

Otti Berger's zebra textile on Aalto's chair no. 39 at the Aalto exhibition in Foreningen Brukskunst, Kunstnernes Hus, 1938.

Photo: Utklipp fra Arbeiderbladet 22.8.1938.

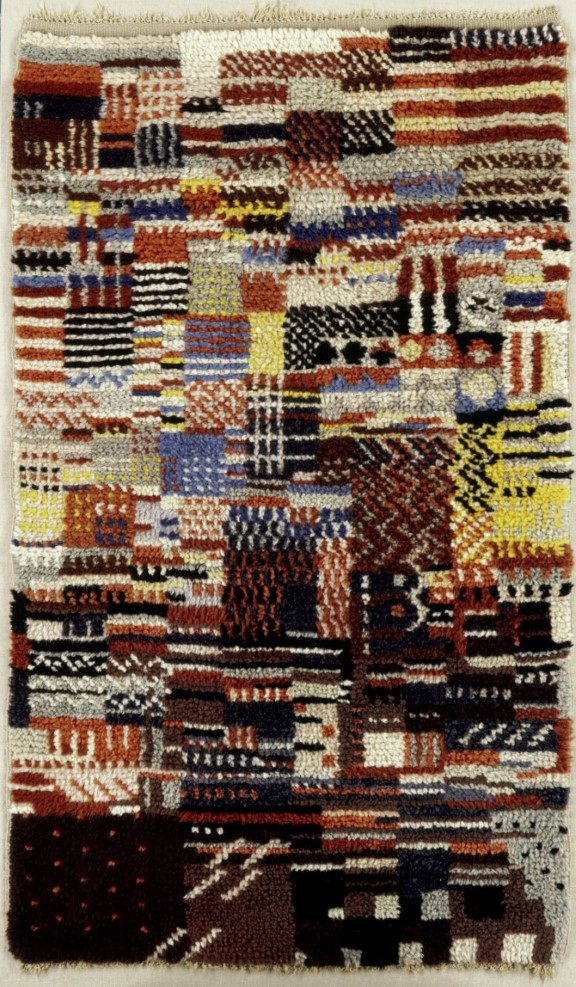

Otti Berger, rya-rug, Bauhaus, 1928–1929.

Photo: Atelier Schneider / Bauhaus -Archiv, Berlin.