Class differences and tensions

Teddy as a source of security

The emergence of Claire

In 1973, Perry discovered a taste for dressing in women’s clothes. This urge was a further source of anxiety, due to the fear of being discovered. He made his first public appearance dressed as a woman in 1975, marking the birth of his transvestite personality Claire, who would also later figure in some of his works. In the same year, he moved in with his biological father and his partner, only to be kicked out again when they discovered his transvestism. In due course, these significant experiences of his younger years, together with his working-class background and the social tensions of Essex as a region, would all feed into his art.i

The road to art

The first works

Provocative messages

Breakthrough

Direct and immediate imagery

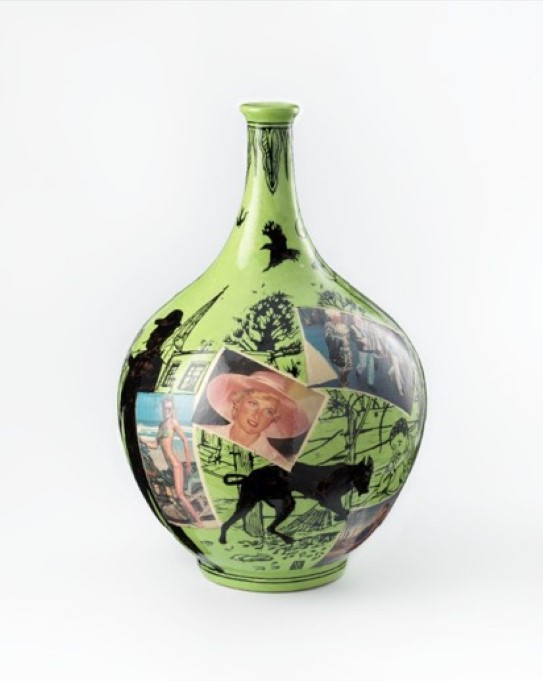

But it is in terms of their subject matter and imagery that Perry’s pots stand out from the crowd. He worked with a combination of transfer images based on popular culture or art history, and his own paintings, which are stylistically indebted to comic strips. A direct and immediate idiom with a recognisable frame of reference. Thematically, his pictures represented – and told stories about – people who challenge social norms through their sexuality or gender roles, or lives marked by violence and anxiety. He depicted people and subcultures on the margins of society, a preoccupation that has become an enduring feature of his art. There is a parallel between his themes and his choice of ceramics as a medium.

As a fine artist who has chosen forms of expression and media that defy the norm, Perry himself can be said to live on the margins of the art world. In his own words: “Pottery is my gimmick,”vii and without doubt it is his ceramic works that have made him famous.

Challenging society’s male ideal

Crossing the boundaries of class

In 1992, Perry married a woman from the middle classes, and this migration from one class to another seems to have heightened his awareness of his own social background and class identity. One of his perennial interests is the ways in which class identity shapes us as individuals and helps to determine our tastes and value systems. The social structures that ensure we all share the same values and fit in as individuals also serve as markers that distinguish one class from another. The fascination with these social phenomena has informed most of his work.viii

Another kind of class division that Perry has encountered concerns the norms and genre hierarchies that govern much of what happens in the art world. As a ceramicist who works with the forms of functional objects, it can be hard to gain recognition in the fine art domain. It is fine art that dictates the norms of the art institution. This is a field in which the artistic idea takes precedence over technique, material, and function. As a rule, a vase is not accorded the status of an artwork.

Despite having made a name for himself as a contemporary ceramicist during the 1990s, Perry did not initially achieve recognition in the fine art sector. His exclusion from the elite circles of the contemporary art world has been a source of both frustration and inspiration, as many of his works illustrate. Perry’s relationship to the art world is ambivalent and he has frequently depicted the superficiality, vanity, and pursuit of status associated with it to satirical and ironic treatment.ix Exclusion, whether in relation to sexuality, identity, or ceramics, can be viewed as an important source of inspiration in his art. He often highlights the things that lurk in the shadow of “normality”, exposing them unfiltered.

In 2003, Perry was awarded the prestigious Turner Prize for his work. In their justification for the decision, the jury highlighted his combination of an uncompromising commitment to the individual and the articulation of societal challenges with traditional ceramics and the use of innovative pictorial narratives. Since the prize was given for fine art, Perry’s status changed overnight from humble potter to fine artist. This gave him access to the most prestigious exhibition arenas, to private art collectors, and the media.

Recognition at last

The unknown craftsman

One characteristic of the early history of fine art and the decorative arts is that we rarely know the names of the people who made the artefacts from those periods. Some of the great masterpieces in the history of art were the work of now nameless craftsmen. Perry honoured these unknown craftspeople in his 2011 exhibition The Unknown Craftsman at the British Museum, where almost every object in the collection was made by someone whose identity is no longer known. Yet it is thanks largely to them that we have access to the cultures of the past. The exhibition highlighted the central significance of craftsmanship in art and human cultural history. Perry’s art and his choice of media are concerned in part with turning a spotlight on genres and techniques that the fine art field has ignored as untrendy in recent decades, media such as printmaking, woodcarving, ceramics, and tapestry weaving, genres where craftsmanship and materials are integral to the aspect of artistic expression.

Over the years, Perry has become an experienced ceramicist who has mastered the methods of hand-building vases and various time-consuming decorative techniques, but when it comes to printmaking, sculpture, and tapestries, he does not carry out the actual crafting process himself. Instead, he delivers designs for the works to specialised workshops and engages in dialogue with the craftsmen and technicians who turn his ideas into reality. The practice of entrusting designs to craft specialists has a long historical pedigree. Regardless of whether he undertakes the crafting process himself or engages the assistance of others, the intersection between craft, materials, and artistic idea is crucial to his work. His stance pays tribute to the artists of past times while simultaneously forging a link to the history of arts and crafts. Materials and techniques also have a story to tell, and in Perry’s universe they create a resonance that reinforces the message of his stories.

The Vanities of Small Differences

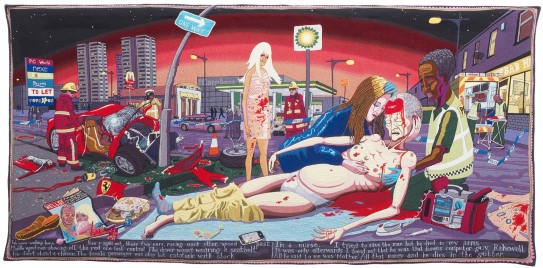

This point is best illustrated by one of Perry’s most important works, the tapestry series “The Vanity of Small Differences” from 2012. This consists of six tapestries for each of which Perry produced a so-called cartoon – a full-sized design for the work, drawn and coloured by hand – which is translated into textiles by a professional weaver. In dialogue with Perry, the design and colours are coordinated and entered into a computer program that controls the actual weaving process. The tapestries are woven on a highly sophisticated Jacquard loom, which produces a three-dimensional effect in the weave. The roots of this technique date back to the medieval period, although its heyday was in the 16th and 17th centuries. This was an exclusive art form, and only the richest could afford to decorate their walls with examples of it. Tapestries woven in this technique are often referred to as Gobelins, named after an illustrious French tapestry workshop in Paris. Gobelins often told a story across a number of separate panels, for example, the progress of the seasons or the Passion of Christ.

Perry’s tapestry series is a retelling of William Hogarth’s (1697–1764) “A Rake’s Progress” (1732–34), a pictorial story in eight pictures. This describes the tragic fate of Tom Rakewell, the son of a successful merchant. Hogarth’s pictures trace Tom’s descent from privileged heir at the start of his adult life through to destitution and madness in a mental hospital. In Perry’s retelling of this story, we follow Tim Rakewell on a journey up through the classes of English society, from working class, via the middle classes, to the upper class. Here as well the story ends tragically with a fatal accident in a red Ferrari.

In his picture series, Perry also includes references to historical religious motifs, invariably rendered with his refreshing and somewhat cartoonish use of line. By constructing “The Vanity of Small Differences” as a classic pictorial narrative in the tapestry medium with religious references, he invests the work with an aspect of monumentality and claims for his own narrative some of the prestige associated with historical Gobelins. The work engages in a complex dialogue between history and the present. The biblical and mythological narratives of classical tapestries are thrust into the background in favour of a social drama from our own day and age. By telling a relatable and topical story about the present through the medium of monumental tapestries, he elevates and expands the meaning of ordinary people and their daily lives. This may well explain why Perry has become public property in the UK. The stories he tells are those of the people at large.

Identity-creating objects for contemplation

The past into the present

Vases decorated with images go far back in time. The material we know best are Greek and Roman painted vases, Persian and Peruvian ceramics, and Chinese porcelain. These objects provide archetypes and motifs that have inspired artists right up to the present. In this respect, Perry draws on a long tradition in ceramics while at the same time participating in a larger group of contemporary artists who work with images on pots. Several of these, like Perry himself, explore the history of objects and traditional motif clusters, thereby bringing the past into the present by introducing contemporary themes, forms of expression, and new interpretations.xi It is an approach that reinvigorates the vase as an object for contemplation and as a status symbol, now as a work of art.

Although vases have historically served as high-value showpieces that were only available to the few, the category also includes mundane items that have been, and still are, used in most homes. As an object that most people are familiar with, the vase is an appropriate medium through which the artist can engage the viewer in dialogue. It does not create distance, and for people with little experience of viewing art or visiting exhibitions, it represents an easily approachable object. The threshold for immersing oneself in the subject matter of the work is fairly low, and consequently the artist can convey his message to a broader audience. From a distance, Perry’s vases appear harmless and elegant, while up close, they are often provocative in terms of their themes and imagery.

Devaluation

Restored status

Observer and commentator

New art market

Hogarth’s picture stories

No one excelled at this socially engaged and commentative picture narrative more than William Hogarth. Conditions in London at the turn of the 18th century were somewhat different from those in other major European cities. England was ruled not by an absolute monarch, but by a parliament, which meant there was greater freedom of speech than elsewhere. Accordingly, Hogarth’s stories were juicier in terms of content than similar work produced in, for example, Paris. In many of his pictures, satire, caricature, humour, and fine art all coincide. And they frequently carry some kind of moral message.

Hogarth depicts the murky, laughable, and conceited aspects of life in the big city. He shows us the depravity and hopelessness of the lower social extreme and the hypocrisy, power, and wastefulness of the higher. There is plenty of humour and satire, not least in his representations of the tastes and lifestyles that define the identities of the various classes. In order to recount the story, the theme is invested with movement and presented as a sequence of events either in a single image or via a series of images.xiv

Social and political sting

- Born 25 March 1960 in Chelmsford, Essex, England

- Distinguishes himself with works in ceramics and textiles

- Receives the Turner Prize in 2003

- Nurtures an anthropological interest in the ways social and cultural status is expressed through taste

- Challenges the hierarchy that places material and craft-based art below art based on ideas

Characteristic features of his art:

- exposure of social power structures, our vanities, and our perceptions of the normal

- challenges to the rigid norms that society, communities, and popular culture impose on men

- visualisation of the myths and the inherited values that form society

- use of incisive satirical imagery in combination with widely recognisable artistic idioms and objects