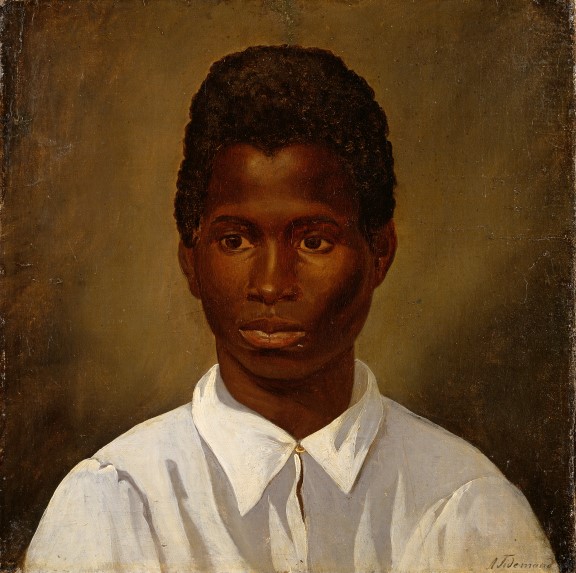

The genre painter Tidemand

More than a quick sketch

In 2003 it was suggested that this painting of the young man may have been painted on the steamship Constitutionen, which sailed from Oslo to Kristiansand. But since Tidemand was actually in Norway in 1841, this could not have been the case. Tidemand did not return to Norway until September 1842. More recently, in 2019, it was claimed that the work was one of the first the artist painted while living in Rome. This is another assertion that cannot be verified, since no mention of the painting has been found by himself or by any of his contemporaries. It is not known where the painting was kept between 1841 and 1925, but in 1925 the National Gallery bought the work for its collection.

The painting is not mentioned in the book Adolph Tidemand: hans Liv og hans Værker from 1878 by the Norwegian art historian Lorentz Dietrichson. This is peculiar, given that Tidemand died only two years before the book was published and that Dietrichson was well acquainted with Tidemand’s works in Norway, including the ones in private collections. It might indicate that the painting was located abroad at the time.

It is not unlikely that Tidemand met the young man, either on a steamship while heading southward, or in Rome. The finished state of the work and its execution in oil on canvas suggest it was more than just a quick sketch made on a ship. It is a fully completed painting, which means he took the time to paint it. It was more than just a quick sketch done with paper and pencil, and was most likely painted in a place where he spent more time, such as in Rome. But it cannot be ruled out he sketched the portrait along the way and then painted it at a later time. The National Museum’s collection holds one more finished sketch painted with oil, but on paper instead of canvas. It is a portrait of a woman named Anunziata, painted on 25 November 1841.

Pilgrims in Rome

Since the Catholic mission was active in many colonial areas in Africa during the 19th century, some of the clerics and pilgrims who came to Rome were black. The Ethiopian church, one of the oldest Christian communities in the world, had its own church and monastery in Vatican City. The church, St Stephen of the Abyssinians, still stands today, and remains one of the official state churches of Ethiopia in Rome.

Depictions of black people in the 19th century