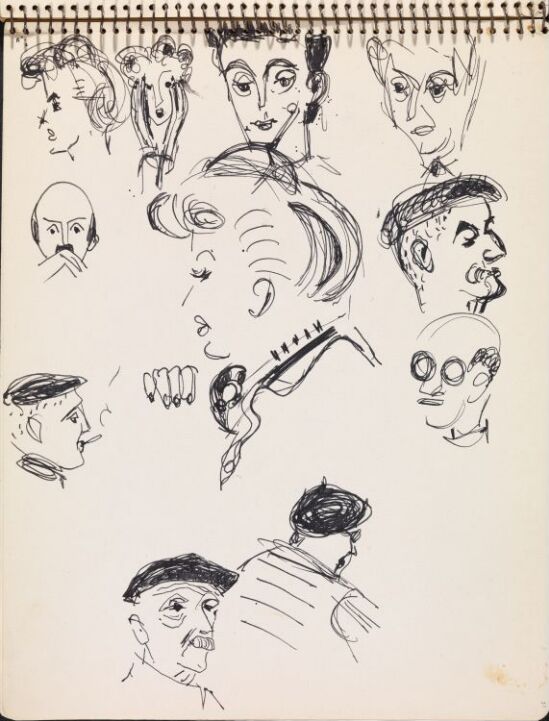

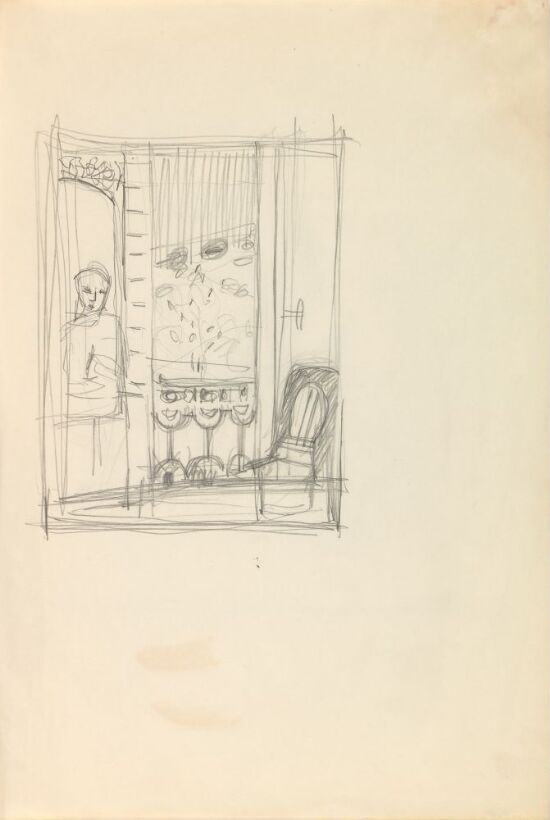

Object type: Drawing

Et kvinnehode og fire mannshoder

- Artist: Erling Viksjø

- Creation date: (1950-tallet)

About

- Creation date:

- (1950-tallet)

- Other titles:

- Et kvinnehode og fire mannshoder (NOR)

- Object type:

- Drawing

- Materials and techniques:

- Blyant og penn på papir

- Material:

- Paper

- Dimensions:

- Height: 27 cm

- Width: 21 cm

- Keywords:

- Visual art

- Classification:

- 532 - Bildende kunst

- Motif - type:

- Figure study

- Inventory no.:

- NAMT.evi158.009

- Cataloguing level:

- Single object

- Acquisition:

- Gave til Norsk Arkitekturmuseum 1999

- Owner and collection:

- Stiftelsen Arkitekturmuseet, The Architecture Collections

- Photo:

- Børre Høstland

- Copyright:

- © Viksjø, Erling/BONO

Nasjonalmuseet's collection catalogue is a living resource of information gathered since the 1830's. Some records may contain language or ideas that today could be perceived as outdated, offensive or discriminatory with regard to for instance gender, sexuality, ethnicity or disability, and that may be at odds with the museum's values regarding equality and diversity.

Do you have suggestions for how this record can be improved? We would like to hear from you!

If you would like more information about specific objects in the collection or about objects that haven't been published online, please contact the museum. You can read more about how we work with the collection and our cataloguing practice here.

Other works by Erling Viksjø

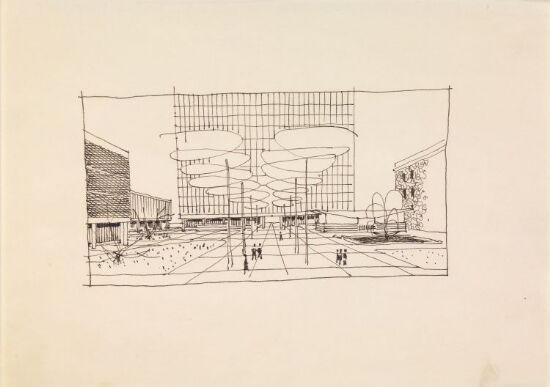

StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet

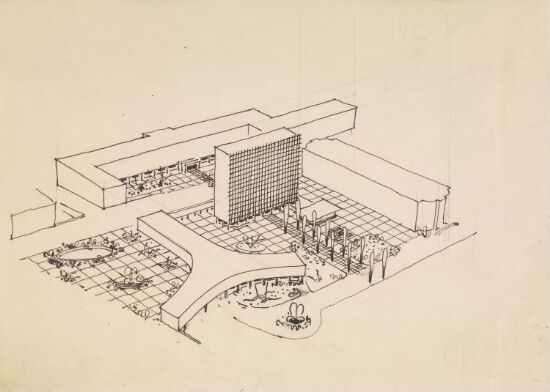

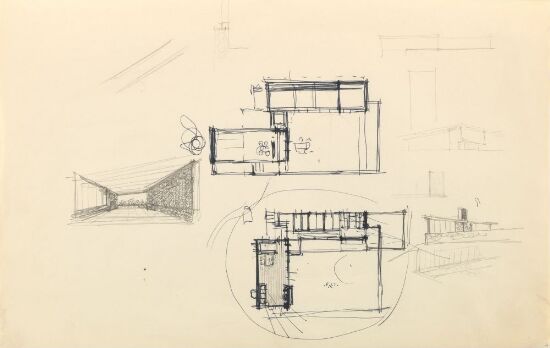

StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet Utbygging av Regjeringskvartalet. FugleperspektivErling ViksjøAntagelig 1958

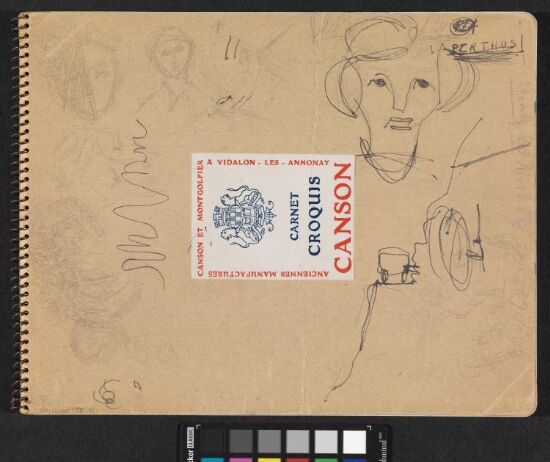

Utbygging av Regjeringskvartalet. FugleperspektivErling ViksjøAntagelig 1958 SkissebokErling Viksjø(1950-tallet)

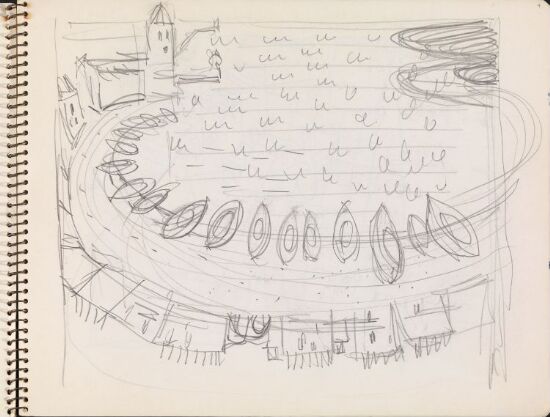

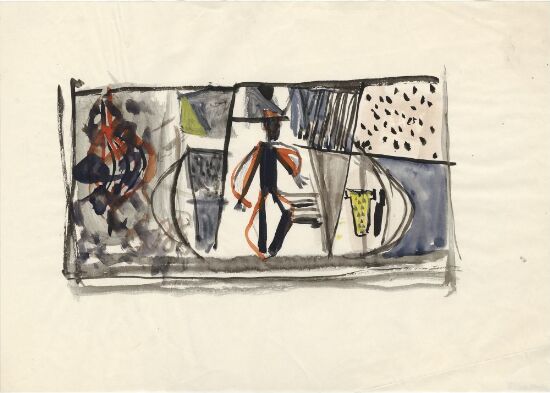

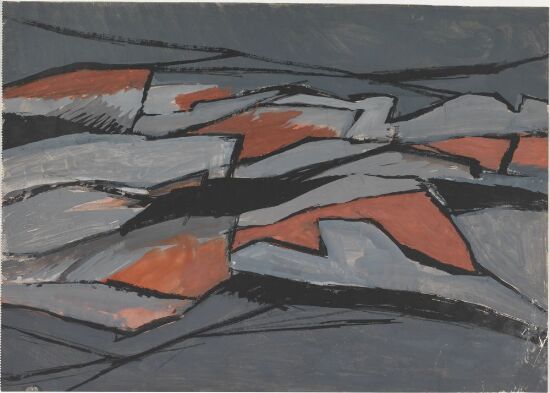

SkissebokErling Viksjø(1950-tallet) FiskerlandsbyErling Viksjø(1950-tallet)

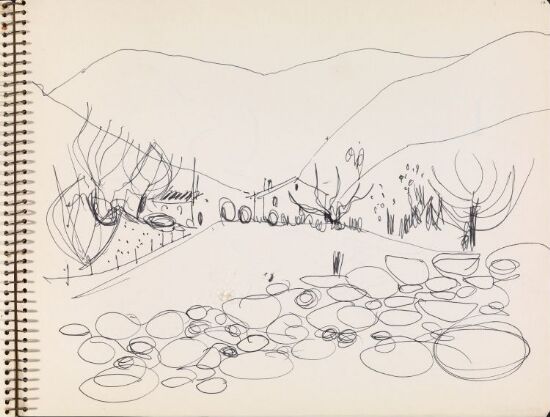

FiskerlandsbyErling Viksjø(1950-tallet) Hus med fjellandskapErling Viksjø(1950-tallet)

Hus med fjellandskapErling Viksjø(1950-tallet) Utbygging av RegjeringskvartaletErling ViksjøAntagelig 1958

Utbygging av RegjeringskvartaletErling ViksjøAntagelig 1958 StudyErling Viksjø1950-tallet

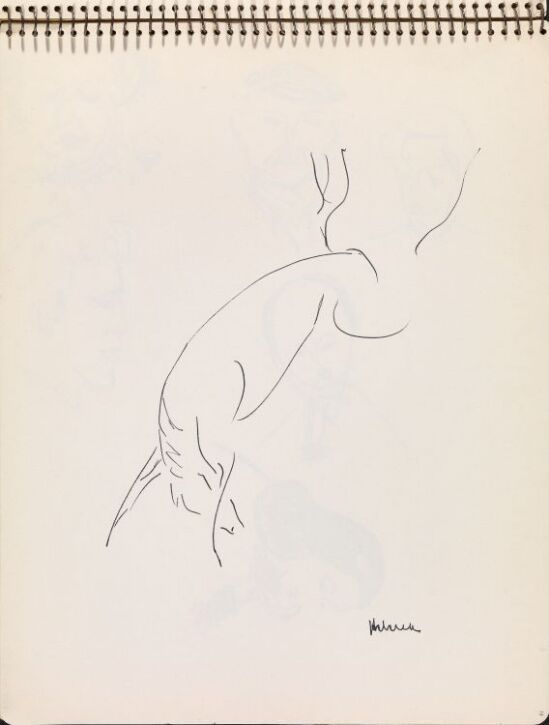

StudyErling Viksjø1950-tallet FigurstudieErling Viksjø(1950-tallet)

FigurstudieErling Viksjø(1950-tallet) KomposisjonsstudieErling Viksjø(1950-tallet)

KomposisjonsstudieErling Viksjø(1950-tallet) StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet

StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet

StudieErling Viksjø1950-tallet Sommerhus i RekkevikErling ViksjøCa. 1956

Sommerhus i RekkevikErling ViksjøCa. 1956

'1' of '12'