By Peder Valle, Collections Registrar

The modern tuberculosis hospital that opened in Paimio, Finland, in 1932 was designed with great care, down to the smallest detail. Not just the building itself but also the furniture and other fixtures and fittings were designed by the young, highly sought-after architect, Alvar Aalto.

The hospital building was seven storeys high, featuring large windows and white facades with a few touches of colour. Slender and majestic, it rose from the pine trees, tucked within the peaceful atmosphere of the forest.

After it became more widely understood how tuberculosis spread, at the end of the 1800s, tuberculosis hospitals were generally constructed in rural areas, well outside the cities. The objective was to ensure that patients had easy access to fresh, healthy air. Sanatoriums, as these institutions were also called, were to be “oases of health”, removed from noise, illness and contagion.

The word “sanatorium” derives from the Latin word “sanare”, which means “to heal”.

A place promoting health

The hospital in Paimio was based on these ideas. The interior was simple and sober, but had strong colours and was equipped with specially designed furniture that was meant to emphasise the primary function of promoting healing and good health. The furniture and fittings, like the building itself, were designed with the well-being of the patients in mind. The gently rounded chairs encouraged patients to lean back and open their airways more fully. The curved porcelain sinks were designed to muffle the sound of the running water.

Useful architecture and design

The tuberculosis hospital in Paimio is an early Finnish example of functionalism, the style that embodied the modernist principles of simplicity and functionality in design. The stylistic idiom of functionalism was meant to reflect the ideals of science and mathematics; design and architecture were to follow the logic of clarity and rationalism. The concept of being fit for purpose – being useful – was a key element. The ideals of modernism influenced several generations of architects and designers.

Alvar Aalto (1898–1970) was a staunch supporter of the theories of modernism. In 1935 he and his wife, Aino Mandelin (1894 –1949), founded the Artek company, which produced furniture, textiles and lamps that they designed. Among other items, Artek manufactured the Paimio Chair, no. 31, which Alvar had designed for the hospital several years earlier. The Museum of Decorative Arts in Oslo purchased one of these chairs and two other pieces of furniture designed by Aalto as early as 1938.

Alvar and Aino travelled to Italy for their honeymoon in 1925 to see architecture from antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. Italy was a popular destination at the time, and a trip there was regarded as a sort of educational journey. What could a modern architect learn by studying the architecture of antiquity? Was it possible to draw inspiration from an ancient golden age when trying to create a new one?

The monuments of the future

Many architects and designers of Aalto’s generation felt strongly that they were on the cusp of a new golden age – a modern, socially just world, which they were helping to create through their work. Schools, factories, power plants and hospitals were to be the monuments of the new age, replacing the palaces, temples and cathedrals of the past. Science and technology were the new religion.

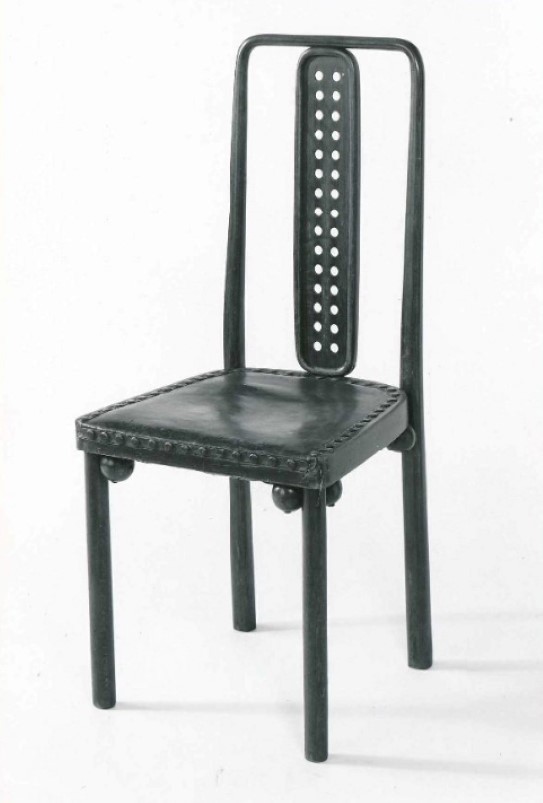

There was a broad consensus that a simple, austere style was best suited to conveying the ideals of a new age. As early as 1904 the Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffmann designed a sanatorium in Purkersdorf, outside of Vienna, in the restrained Viennese version of Art Nouveau called the Vienna Secession movement. Hoffmann also designed furniture and fittings for the building, as Aalto would for his sanatorium many years later. This was entirely in line with the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, which was a guiding force within design and architecture in the period around 1900.

“Gesamtkunstwerk”, from German, means “total artwork” and implies that all art forms should interact with each other, thus producing a higher entity. Within design and architecture this generally means that all the components and details are designed by one person, using the same template.

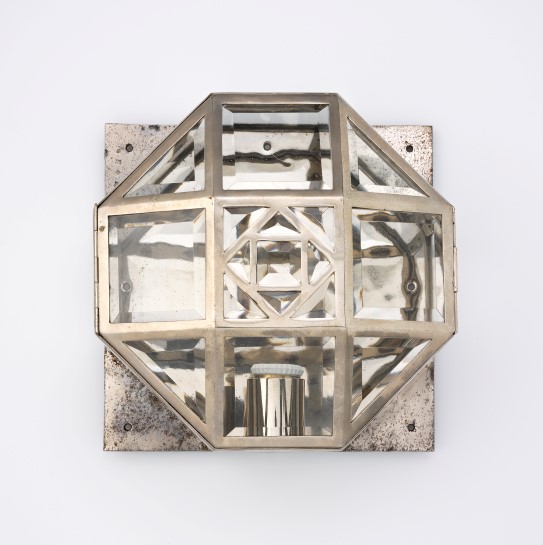

In Purkersdorf, Hoffmann presented an early version of an aesthetic movement that, a century later, is commonly associated with the health sector, and which is often typical of hospital and laboratory environments: white surfaces and nickel-plated metal, simple designs with austere and ascetic ornamentation. The white, clinical interior has become the very symbol of health, treatment, cleanliness and convalescence. Why is this the case?

White castles – palaces of cleanliness?

The development of modern medicine and bacterial science in the 19th and 20th centuries is an important part of the explanation. Hospitals were no longer merely repositories for society’s outcasts. The modern hospital became a place where patients received increasingly advanced treatment, and recovered – a castle of technology and science. It became standard to decorate hospitals in white or green, colours that are associated with calmness, light and cleanliness. Naturally, this had a practical aspect, too: what was white looked clean, and clean meant free of bacteria. Dust and dirt were easily visible when daylight flowed in through large windows and lit up the white interior.

The healthy environment also had to be easy to clean properly. With the laboratory as a model, a view emerged in the early 1900s that simple forms and unornamented surfaces were most practical in the battle against bacteria. Simplicity now became even more clearly a symbol of cleanliness.

Ornament and crime

Similar ideas were expressed by one of Josef Hoffmann’s contemporaries, the Austrian architect Adolf Loos. In 1910 he gave a lecture, “Ornament and crime” (German: Ornament und Verbrechen), in which he described the desire for decoration as “primitive”. Loos regarded the elimination of ornament as a key element in the development of a modern design culture.

Loos’s argument was easy to understand. In all contexts it became the norm to refer to simple, unornamented forms as “clean”. The quality of being simple was equated with being rational and healthy, and here the parallels with modern epidemiology are apparent. In 1935 Thor B. Kielland, director of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Oslo, stated that “the healthy functionalism is our watchword. No more plush fabrics, elaborate trimmings, turned wooden knobs, lavish carving and half-dead palm trees that collect dust and create unnecessary work. We demand simple, straightforward designs […] that are easy to keep clean.” Kielland’s words make it clear that aesthetic and hygienic health had been merged into two sides of the same coin.

The morality of design

This line of reasoning continued to permeate professional journals and magazines far into the 20th century. Everything from door handles to breakfast dishes was to be simpler, often with little decoration or none at all. Bacterial science essentially paved the way for broader acceptance of modernist views. Arguments promoting cleanliness and health shaped generations of architects and designers, who approached their task reverently. The question of design evolved into a moral question: creating something “clean” was producing something that was healthy and good. It was taking the moral high road.

With the advent of antibiotics, tuberculosis in Europe was ultimately defeated, and Aalto’s modern tuberculosis hospital became outdated as early as the 1960s. In the 1970s the building was re-tasked as an ordinary hospital. Today the facility has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is best known as one of Alvar Aalto’s major works. Architecture devotees from all over the world flock to Paimio to see how the famous Finnish architect brought modern hospital design to the architectural agenda. The idea of health, cleanliness and simplicity still lives on today, not just in hospitals and the health sector, but in society at large, and in our own perceptions of architecture and design. Can “good” design quite simply be healthy? Aalto and his contemporaries, at any rate, were convinced that this was the case.

Sources:

- www.alvaraalto.fi

- Marianne Heikinheimo. Architecture and technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium. PhD thesis, 2016.

- Ellis Woodman. Revisit: ‘Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium continues to radiate a profound sense of human empathy’. 2016.