To Draw a Text

Liberation

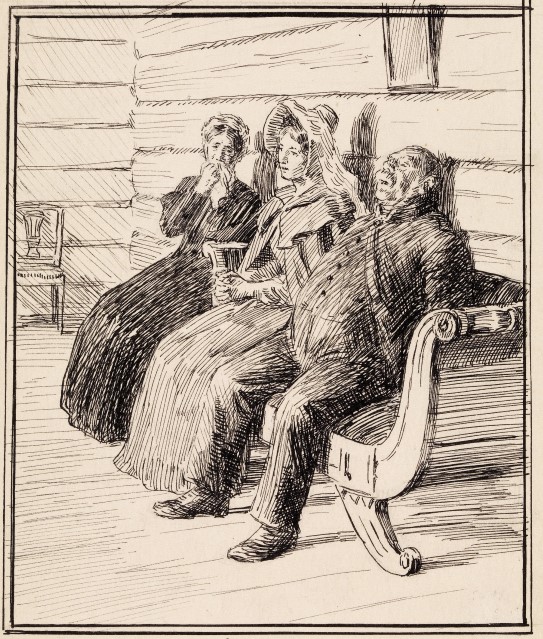

In the illustration "And There She Sat in the Drawing Room" (Og der inne i stuen satt hun, figure 1), we see the immediate reactions to an important, pivotal moment in "The Family at Gilje": The middle daughter of the three, Inger-Johanna, has come home unexpectedly to deliver the news that she has cancelled her wedding to the high-standing captain, and that she is in love with the poor radical, Grip. The three figures in the drawing express resignation, sorrow, concern, and relief, all at once. The parents are marked by worry and pessimism about the future. Their dashed hopes can be read on their faces, hopes for their daughter’s future, the family’s reputation, and fewer bills to pay. Inger-Johanna’s interwoven fingers evince her inner turmoil in anticipation of their meeting, and yet the relief in her facial expression displays hope for the future.

The scene in this illustration does not exist in written form. In the text, the father sits with his hands on his knees and stares at the floor before getting up and remaining standing. Werenskiold has instead chosen imagery that captures the emotions of the drama in this scene, and the illustration represents a greater segment of the book compressed into a single image.

Illustration or decoration?

Women Tying Garlands (Kvinner binder girlander, figure 2) is a vignette (a small drawing at the beginning or end of a chapter)[i]. It does not depict any concrete situation from the book, but a connection to the text exists in the motif, which represents one of the book’s recurring themes: the woman’s position in the home. For women in a family like the one at Gilje, the working day consisted of doing the same household chores day in, day out. The handwork hanging in bows between these working women resemble garlands, and the women themselves are like sculptures blending into the surroundings as if on a side stage. They are doing a repetitive task that is in turn rendered in a repeating, ornamental style. This vignette is thus not merely decorative; it evokes central themes of the novel and can be viewed therefore as somewhere between decoration and illustration.

Longing

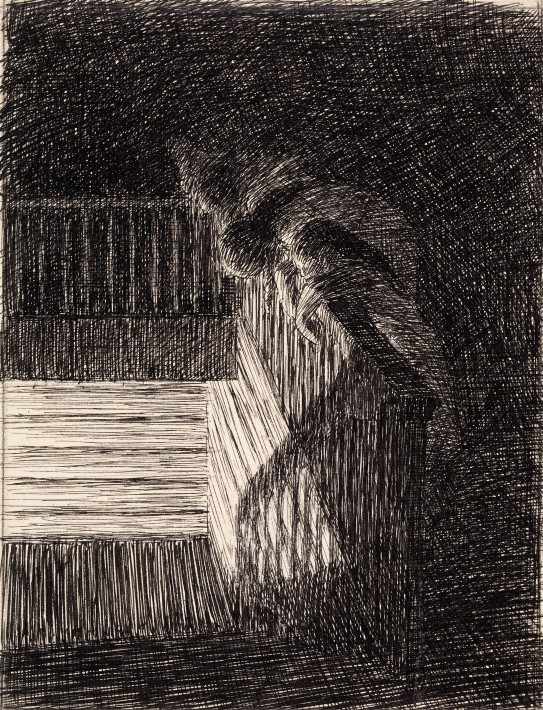

Another recurring theme in the novel is the great gulf between the girls’ life in the hamlet and independent adult life out in the larger world. In "The Sisters Leaning Over the Railing" (Søstrene lente seg utover rekkverket, figure 3), Werenskiold has illustrated a situation in which the young sisters have been banished to the second floor of the house, to the darkness. They lean over the railing toward the illuminated area of the floor below, stretching to hear the conversations, brought in by guests for the evening, about the world beyond the village: “All their thoughts and longing were fixed on the strange distant world that so seldom visited them, but about which they heard much that sounded grand and adventurous.”The light area of the drawing represents the sisters’ desires and dreams of escapades in the city and an exciting future. The railing between the girls and the light seems, however, insurmountable: both social and economic factors are behind this symbolic obstacle. The daughters’ prospects were limited, and they were dependent upon either inheriting money or marrying well. There was no great inheritance in sight, and thus little chance that they would have the freedom to choose their own lives. Inger-Johanna, however, stood to inherit from an aunt and was therefore somewhat freer. She never marries. The mother in the family, “Ma”, sums up the situation: “Only the very fewest of us women get to choose what we want.”

The contrast between a preliminary sketch (figure 4) and the finished illustration is pronounced in Werenskiold’s treatment of details and light/shade. The dark areas and the simplified bodies in the finished work supplant the detail in the preliminary sketch, tightening the effect. The three children’s forms merge into the complete darkness, giving the impression of something intangible and mysterious. It is the contrast between light and shade, an effect usually called chiaroscuro, that dominates.

Reconciliation

In Thinka and Inger-Johanna at Home at Gilje (Thinka og Inger-Johanna hjemme på Gilje, figure 5), the sisters are outside, standing close to one another and chatting. Several years have passed since they stood together on the second floor and leaned hopefully toward life beyond the hamlet. They have experienced what adult life had to offer them, and their childhood expectations have faded with the years: “The sisters were together again, talking as in the old days; but neither of them wondered anymore what there was to find in the world beyond theirs... They both knew now!”

In contrast to the abstracted scene in "The Sisters Leaning Over the Railing", in which the girls are straining toward adult life’s captivating sounds, smells and light, this illustration is almost completely without shadow. The two figures meld seamlessly into their surroundings. Absent the striking chiaroscuro, the drawing appears restrained, more like an evocative rendering of nature than a dramatic culmination. Adult life and “big city life” have been revealed and demystified.

With a simple pen or pencil, Werenskiold conveys nature and interpersonal relations with great sensitivity. In his sober depictions of nature, figure groupings are often placed to the side and merge discreetly with the environment. Where people are the central focus of the illustration, daily life and profound emotions are conveyed in ways that feel familiar. "The Family at Gilje" has been called “the richest, most finely illustrated book that any single Norwegian artist has accomplished.” Although well over one hundred years old, the illustrations for this novel appear timeless, and they are well worth becoming more closely acquainted with today.